‘She was twice apprehended marching towards the end of the Yarra Street Pier, once with a large barracouta in her possession.’

By Victoria Spicer

Johanna Spicer formerly Kennedy nee Ryan entered my life in 1994. She arrived in an envelope marked Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages Victoria, a name inscribed in cursive script on a crisp A3 certificate. She’d been dead more than 90 years. This is her story.

*

I called Joseph Spicer the grey sheep of my family. I wasn’t sure whether he was bad, foolish, luckless, or all three. Born into a poor Market Harborough family in about 1817, he was ‘unchurched’ and unschooled in little other than thieving. In 1840 he was sentenced to four months imprisonment with hard labour in Leicester Borough Gaol for stealing 30lb of lead, value five shillings, from the roof of a house. He emigrated to Victoria in 1853, established a short-lived brickworks at Strawberry Hill near Geelong and joined the temperance society. But what most piqued my loquacious fascination was his six ‘wives’.

I unraveled Joseph’s story in the opaque pre-internet era. During long days at London’s St Catherine’s House, I heaved and thumped elephantine volumes of birth, death and marriage indexes onto benches and flipped their wide pages, my eye tracking my finger down the rows of names. A procession of wives arrived in my letterbox on certified green, orange and grey GRO paper – Mary Burrows, married 1838, died 1839; Ann Brown, common law wife – their child, Priscilla, born and died 1842; Ann Goode, married 1844, presumed separated soon after; and Elizabeth (Betsy) Barnacle. When Joseph and Betsy married in 1848, his condition was recorded as bachelor!

Betsy drowned crossing a flooded Waurn Ponds Creek in September 1853, less than three months after their arrival in the colony. In October 1854, Joseph married my great great grandmother, Sarah Beaton (aka Marion Bethune), a native of the Isle of Skye. Their union lasted 24 years, until Sarah’s death from consumption in 1878; and my great grandfather, Archibald Spicer (1855-1944) was the eldest of their five children.

Johanna Kennedy nee Ryan was ‘wife’ number six. Joseph had been a widower thirteen years when they married at Christ Church Geelong on 27 April 1891. Both parties gave the Reverend an air-brushed version of themselves. Joseph is recorded as Julius, age 50 (actual 74), the bride is 41 (actual 56). I dined out vociferously on my research stories, the six wives of Joseph Spicer eliciting the best jaw-dropping responses. While I was genuinely amused by Joseph’s antics – partly because he was the complete antithesis of the heroic Joseph Spicer my father had regaled me with stories of – I was also sad and confused. Was the marriage hastily arranged? Alcohol fuelled? If Joseph hadn’t fallen off the temperance bandwagon, perhaps he’d been struck down with dementia. He’d forgotten his name, his age, his many marriages and most of his children. And what kind of woman would marry a man 74 and failing?

Joseph and Johanna were living in Union Street, Geelong, a narrow seedy backstreet, in late June 1891, when their activities came to the attention of police. They were charged under the Vagrancy Act ‘with being the occupiers of a house frequented by idle and disorderly persons … [where] conduct of a grossly immoral character had been carried on’. A full twelve column inches of the Geelong Advertiser’s page 2 ‘Town Talk’, was devoted to the story, an article that is light on descriptive detail, heavy on strong moral language. Words like sex or prostitution wouldn’t sully the lips of respectable people or the pages of a good newspaper, but the word ‘brothel’ and that ‘the female prisoner, whose real name was Kennedy, was an old offender’ leapt out at me.

I imagined the hand-wringing, eye-rolling and tut-tutting of Joseph’s despairing son Archibald, founder and elder of the local Methodist church, member of the Temperance life boat crew and businessman. There were no further charges of vagrancy. Joseph and Johanna moved to a cottage in Belmont owned by Archibald. In the early hours of 4 June 1895, it burnt to the ground.

I told their story laughingly to stiff and proper relatives who wanted worthy ancestors to pedestalise. They’d look at their feet, they’d shuffle silently away, their interest in family history instantly quelled.

*

Twenty years later, retrieving the sheaf of documents and scribbled notes I’d made about Johanna, I was struck by how little I really knew about her. There was evidence of my cursory attempts to find out more, but the dizzying number of variants of her name – Johanna, Janna, Hannah, Honora, Ann, Anna, Annie – and the ubiquity of the surnames Kennedy and Ryan, had defeated me. I was conscious too that I’d judged her abruptly and sensationalised the fragments I’d found. Tumultuous events in my own life in the intervening years had softened me. When I searched again for Johanna in 2014, it was with a mind more open and empathic.

Johanna was born in Hollyford, County Tipperary, Ireland, in 1835, the eldest child of Cornelius Ryan and Bridget nee Leonard[i]. An extended family of Ryans, which included sister Catherine, born c1839 and an uncle (Patrick) and aunt (Mary) arrived in Port Phillip Bay as bounty immigrants aboard the barque Enmore on 4 October 1841. Connor and Biddy and their growing family lived first in the Merri Creek area north of Melbourne, where they were employed as farm worker and servant. By 1847 they’d settled permanently in Geelong. On 19 May 1851, Johanna, perhaps not yet sixteen, married Thomas Kennedy, a labourer more than twice her age.[ii]

The Gold Rush which began soon after changed everything. The Kennedys and Ryans pooled their resources and relocated to Ballarat in about 1853 – and struck gold. By April 1854 they’d returned to Geelong with enough money to buy property; not fabulously wealthy, but comfortably well-off.[iii] Thomas bought two parcels of land, 29 and 25 acres, at Moolap, near Lake Connewarre, built a small house, cleared, fenced and began to farm the land. By 1864 Thomas and Johanna’s family comprised six children – Bridget (1852), Mary (1854), John (1856), Cornelius (1859), Michael (1862) and Catherine (1864).

On 12 November 1866, Johanna was visiting a neighbour, the older children were at school, and Thomas was at home looking after Michael, five, and Catherine, almost three. Shortly before two o’clock he stepped out for a walk, leaving the children alone. During his absence, little Catherine’s dress caught fire. She’d been sitting on the bricks beside the fire, her brother said, and some cinders set her dress alight. ‘All that remained of the dress was a strip of cloth hooked around her neck’, her body blistered and seared. She was taken to the hospital, barely alive, but died a few hours later.[iv]

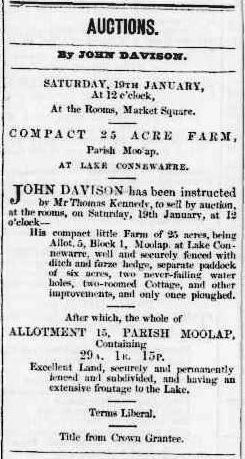

In January 1867, two months after Catherine’s death, Thomas sold their ‘compact little farm of 25 acres … well and securely fenced with ditch and furze hedge, separate paddock of six acres, two never-failing waterholes, two-roomed Cottage, and other improvements, and only once ploughed’ and a further lot of 29 acres.[v] I wondered, was the sale precipitated by grief or financial difficulties? Finding no evidence of the latter, I imagined Johanna’s country haven haunted by the ghost of Catherine and her agonising death.

I found the site of the farm on an old parish plan, identified its present-day location on Google Maps, and drove out to take a look. This part of what is now Leopold is still semi-rural, with homes on acreage. The farm, which remains a discernible entity, is surrounded by fences and trees, but unoccupied, eerily bare. Though the land is flat and Lake Connewarre, the north-western edge of which is only about 300 metres away, is hidden from view, it has the feel of a rural idyll. I couldn’t imagine it being abandoned lightly.

Thomas and Johanna and their children moved into Geelong in early 1867 and rented a small cottage; almost every year thereafter they moved to another of similar size and value. The lingering grief and trauma of Catherine’s death is evidenced in cemetery records and birth indexes. Her little body was exhumed from the Geelong Eastern Cemetery on 15 August 1867 and reburied in Melbourne.[vi] No children were born to Thomas and Johanna for seven years, from 1864 to 1871. Then four arrived in quick succession: twins Catherine and Johanna (1871), Annie Florence (1873) and Alice Augusta (1875).

When Thomas was admitted to hospital with paralysis in 1875, the family got by with the contribution of 17 shillings each week from the wages of two grown up daughters. Six months later, in March 1876, Johanna too was hospitalised for rheumatism; two of the children, nineteen and five years of age, were in the hospital also. Twenty-one year old Mary left her position to care for the two youngest children. In April 1876 Alice Augusta Kennedy, aged two years, and Annie Florence Kennedy, twelve months old, were charged with being neglected children, made Wards of the State, and sent to an institution in Melbourne.[vii]

The Geelong Advertiser reported that Sergeant Morton, who visited the house in Ashby, ‘found [it] very clean and tidy, but there were no provisions in it with the exception of a little arrowroot, which had been sent by a neighbour.’[viii] The St Vincent de Paul Society, which had provided assistance initially, withdrew it when they heard that the State would take care of the children. Johanna’s extended family – parents, siblings, uncle, cousins who lived nearby – were notably absent.

The first publicly available evidence of Johanna’s drinking appears in the aftermath of the children’s removal. Geelong Infirmary Admission Books show she was admitted three times between November 1876 and December 1878, twice for alcoholism; each time they proclaimed her ‘cured’ upon discharge two weeks later.

Thomas died in 1879 and the older children drifted away. I imagined Johanna alone, perhaps working as a servant, perhaps as a prostitute, perhaps both. Throughout the 1880s and early 1890s she was arrested more than twenty times and fined, then jailed in lieu of payment, for being drunk and disorderedly in a public place. In 1889 she was jailed for six months for being ‘a habitual drunkard’. Sometimes she was so incapacitated she had to be carted to court in a handcart or a cab. She was twice apprehended marching towards the end of the Yarra Street Pier, once with a large barracouta in her possession.

During the four, almost five years she was married to Joseph, her drinking binges were less frequent. When their house burnt down and when Joseph died, on Christmas Day 1895, the newspapers wrote about them both in such a kindly manner, Joseph and Johanna became, for that moment at least, just an elderly couple living quietly together, gardening for a living.

For the first eleven months of 1896 following Joseph’s death, Johanna lived uneventfully in Marshall St, Chilwell in a cottage her step-son Archibald, who lived a few doors away, may have helped secure. In late November 1896 she was fined ‘5s, in default 24 hours’ imprisonment’, for drunkenness and in February 1897, she ‘narrowly escaped a walk over the end of the Yarra-street pier, upon which she had ventured in the belief that she was going to Belmont via Barwon Bridge’.

Then she disappeared. The regular mentions in the Geelong Advertiser’s ‘Town Talk’ ceased.

I searched the asylums, hospital, courts and cemeteries. I scoured registers of deaths, inquests and newspapers. There was no trace of her – not a trace. I imagined her staggering down the Yarra Street Pier, her petticoat swishing, a fish under her arm. I imagined her walking into the water and sinking to the bottom of the bay, pulled down by the weight of a bottle in her pocket. I wrote a poem about her, referencing Kenneth Slessor’s Five Bells. But unlike Joe Lynch, no one noticed Johanna gone.

In August 2015, when the Public Record Office Victoria made a digitised Central Register of Female Prisoners available online, I found her. I found her in Melbourne – jailed on three separate occasions for twelve weeks, once in 1898 and twice in 1900, under the Vagrancy Act, for having no visible means of support. It was a crime to be homeless, a crime to be destitute. On 9 August 1900 she was transferred ‘by special authority’ to Bendigo Benevolent Asylum, where she died on 11 August 1902.

During her lifetime, Johanna was a social pariah. The moral code of the day blamed her for her poverty and her alcoholism. Her family abandoned her, she lost three children in tragic circumstances, and the others moved away. I hope her descendants find her; and I hope they regard her life, its grief and trauma, and her failings, with compassion.

[i] National Library of Ireland, ‘Kilcommen | Microfilm 02506/04’, Catholic Parish Registers at the NLI, viewed on 25 August 2019, https://registers.nli.ie/registers/vtls000632735#page/94/mode/1up

[ii] Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages Victoria, Marriage: Thomas Kennedy and Anne Ryan, 1076/1851

[iii] Geelong Advertiser and Intelligencer, ‘Government Gold Escort’, Thursday 13 April 1854, p4, viewed on 25 August 2019, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/page/8163826

[iv] PROV, VPRS 24 Inquest Deposition Files, Unit 185, 1866/332 Female (digitised copy, viewed online 25 August 2019)

[v] Geelong Advertiser, ‘Auctions’, Thursday 17 January 1867, p3, viewed on 25 August 2019, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/page/17540174

[vi] Geelong Cemeteries Trust, Geelong Eastern Cemetery Exhumations, viewed on 5 August 2019, https://www.gct.net.au/deceased-search/; email correspondence, 9 August 2019

[vii] Geelong Advertiser, ‘Police Court’, Monday 3 April 1876, p3, viewed on 25 August 2019, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/page/17546999

[viii] Geelong Advertiser, ‘Police Court’, Monday 3 April 1876, p3, viewed on 25 August 2019, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/page/17546999

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Victoria Spicer, a former research librarian and heritage coordinator at the Victorian Parliamentary Library, has been doing family history (her own and others) for more than 30 years. She wrote a masters thesis on the then new phenomenon of digital genealogy in 1996 and studied Scottish Family History at the University of Stirling in 1997.

‘Finding Johanna’, a story about Victoria’s Irish step-great-great-grandmother, was runner-up in the 2019 Genealogical Society of Victoria Writing Prize.

Jenny Hurley

Congratulations, Victoria, on a superbly written and tenaciously researched story! I can see why it did so well in the Genealogical Society prize.